Butterfield’s Masterpiece

A stone’s throw from the bustle of Oxford Street, the spire of All Saints stands in silent witness. Its courtyard leads into a place which is both intimate and powerful; a place of awe and wonder, of silence and prayer. All Saints Church is here to witness to that Christian faith which its architecture so gloriously expresses.

“I was aware that I was standing not only in one of the great monuments of Victorian church art, arguably William Butterfield’s masterpiece, but also in one of the penultimate expressions of its revived faith within a tradition which stretched back to the Caroline divines in the seventeenth century, down through the Oxford Movement in the nineteenth to our own day.”

Art historian Roy Strong, on his first visit to All Saints

“It is the first piece of architecture I have seen, built in modern days, which is free from all signs of timidity or incapacity…it challenges fearless comparison with the noblest work of any time. Having done this, we may do anything: there need be no limits to our hope or our confidence.”

Art commentator John Ruskin

These two quotations are an appropriate place to begin a survey of All Saints, Margaret Street. Both encapsulate the sense of awe and holiness that greets worshipper and visitor alike.

Both also set All Saints within a historical context – liturgically and architecturally. The Ruskin quotation in particular also hints at the response to All Saints upon its unveiling. Like all great things, All Saints provoked – and continues to do so – a variety of reactions, both positive and negative. Not everyone in the mid-19th century saw freedom from timidity as a good thing.

It is not possible, nor would it be accurate, to divorce the architecture from the history and worship of All Saints. That all should be deeply entwined was a fundamental principle behind the foundation and design of the church. The following pages will trace its history, from its origins as a model church for the Ecclesiological Society, to the architecturally fascinating, decoratively beautiful, but most importantly alive and spiritually enriching place of worship that we have today.

John Betjeman and All Saints Margaret Street

“It was here, in the 1850s, that the revolution in architecture began…It led the way, All Saints Margaret Street, in church building.”

In the 1970 BBC Television programme, Four With Betjeman – Victorian Architects and Architecture,

Sir John Betjeman, the poet, writer and enthusiastic advocate of heritage and architecture, visited All Saints Margaret Street.

Beginnings of All Saints

The church owes it origins to the Cambridge Camden Society (from 1845, the Ecclesiological Society) founded in 1839 with the aim of reviving historically authentic Anglican worship through architecture. Its influence was substantial, and by 1843 its 700 members included the Archbishop of Canterbury. Its monthly magazine, The Ecclesiologist, reviewed new churches and assessed their architectural and liturgical significance.

In 1841, the society announced a plan to build a ‘Model Church on a large and splendid scale’ which would embody important tenets of the Society:

- It must be in the Gothic style of the late 13th and early 14th centuries

- It must be honestly built of solid materials

- Its ornament should decorate its construction

- Its artist should be ‘a single, pious and laborious artist alone, pondering deeply over his duty to do his best for the service of God’s Holy Religion’

Above all the church must be built so that the ‘Rubricks and Canons of the Church of England may be consistently observed, and the Sacraments rubrically and decently administered’.

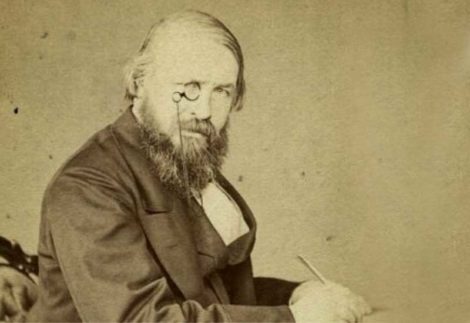

The project was supervised, and largely sponsored on behalf of the society, by Alexander Beresford-Hope, later MP and son-in-law of the Marquis of Salisbury, who chose the architect William Butterfield (1814-1900) to undertake the project (though the two were often to disagree about important aspects of the work).

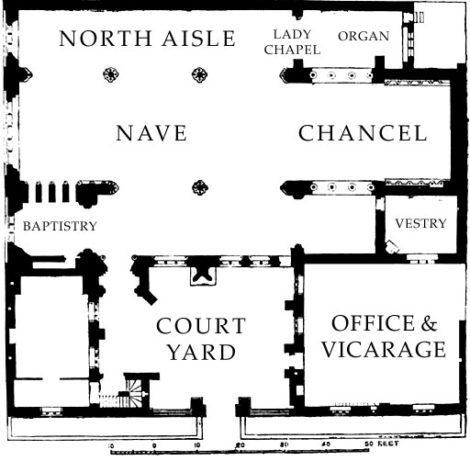

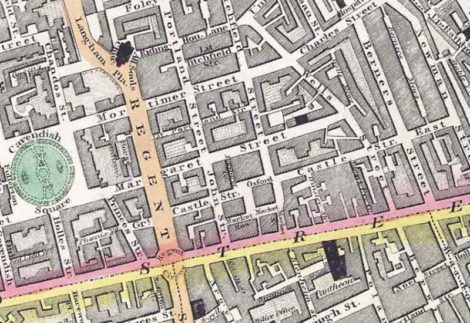

A chapel had stood on the site – midway along Margaret Street, which runs parallel to the eastern half of Oxford Street – since the 1760s, which from 1839 had been used by a Tractarian congregation, and who agreed that the Ecclesiological Society’s model church could be built there. The site was small – just 100 feet square for a church, choir school and clergy house.

All Saints is built of brick. The Ecclesiologists had originally extolled the virtues of rough stone walls, but were converted by the brick churches of Italy and North Germany. The pink brick chosen by Butterfield was actually more expensive than stone. The bold chequered patterning is most likely to have been based on English East Anglian tradition.

Soaring above the courtyard is the 227-feet spire – higher than the towers of Westminster Abbey.